Push policy»

Git push policies are triggered on a per-stack basis to determine the action that should be taken for each individual stack or module in response to a Git push or Pull Request notification. There are three possible outcomes:

- track: Set the new head commit on the stack or module and create a tracked run (one that can be applied).

- propose: Create a proposed run against a proposed version of infrastructure.

- ignore: Do not schedule a new run.

You can create sophisticated, custom-made setups using push policies. We can think of two main (not mutually exclusive) use cases:

- Ignore changes to certain paths. This is something you'd find useful both with classic monorepos and repositories containing multiple Terraform projects under different paths.

- Apply only a subset of changes, such as only commits tagged in a certain way.

Git push policy and tracked branch»

Each stack and module points at a particular Git branch called a tracked branch. By default, any push to the tracked branch that changes a file in the project root triggers a tracked run that can be applied. This logic can be changed entirely by a Git push policy, but the tracked branch is always reported as part of the stack input to the policy evaluator and can be used as a point of reference.

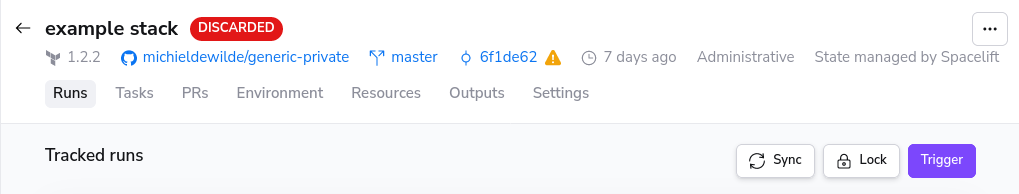

When a push policy does not track a new push, the head commit of the stack/module will not be set to the tracked branch head commit. Sync the tracked branch head commit with the head commit of the stack/module by navigating to that stack and pressing the sync button.

Push and Pull Request events»

Spacelift can currently react to two types of events: push and pull request (also called merge request by GitLab). Push events are the default; even if you don't have a push policy set up, we will respond to those events. Pull request events are supported for some VCS providers and are generally received when you open, synchronize (push a new commit), label, or merge the pull request.

In some cases, Spacelift can receive both push and pull request events at the same time. Review the data input schema and how rules are evaluated to ensure your push policies perform as expected.

There are some valid reasons to use pull request events in addition or instead of push ones. For example, when making decisions based on the paths of affected files, push events are often confusing:

- They contain affected files for all commits in a push, not just the head commit.

- They are not context-aware, making it hard to work with pull requests; if a given push is ignored on an otherwise relevant PR, then the Spacelift status check is not provided.

Here are a few samples of PR-driven policies from real-life use cases, each reflecting a slightly different way of structuring your workflow.

First, let's only trigger proposed runs if a PR exists, and allow any push to the tracked branch to trigger a tracked run:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

1 2 3 4 5 | |

If you want to enforce that tracked runs are always created from PR merges (and not from direct pushes to the tracked branch), you can tweak the above policy accordingly to ignore all non-PR events:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Here's another example where you respond to a particular PR label ("deploy") to automatically deploy changes:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Info

When a run is triggered from a GitHub Pull Request and the Pull Request is mergeable (meaning there are no merge conflicts), we check out the code for something called the "potential merge commit". This virtual commit represents the potential result of merging the Pull Request into its base branch and should provide higher quality, less confusing feedback.

Deduplicating events»

If you're using pull requests in your flow, Spacelift might receive duplicate events. For example, if you push to a feature branch and then open a pull request, Spacelift first receives a push event, then a separate pull request (opened) event. When you push another commit to that feature branch, we again receive two events: push and pull request (synchronized). When you merge the pull request, we get two more: push and pull request (closed).

Push policies could resolve to the same actionable (not ignore) outcome (e.g. track or propose). In those cases, instead of creating two separate runs, we debounce the events by deduplicating runs created by them on a per-stack basis.

The deduplication key consists of the commit SHA and run type. If your policy returns two different actionable outcomes for two different events associated with a given SHA, both runs will be created. In practice, this would be an unusual corner case and a reason to revisit your workflow.

When events are deduplicated and you're sampling policy evaluations, you may notice that there are two samples for the same SHA, each with different input. You can generally assume that the first one creates a run.

Pull Request ID Availability»

When a git push occurs on an open pull request, the push policy receives two events: a git push event that has pull_request: null in its input and a pull request event that contains the pull request data. The default push policy triggers on both events, but due to the deduplication logic described above, the two events are considered the same, and the system retains the first event (the push event without pull request data) and discards the later one (the pull request event with pull request data).

This means that notification policies and other downstream processes never see the event with the pull_request_id field, which can cause issues when trying to target specific pull requests for comments.

Ensuring Pull Request ID is Available»

To ensure the pull_request_id is available in notification policies, you can modify your push policy to ignore the push event without pull request data:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

However, this approach has a side effect: it will ignore push events when there is no pull request. This means that direct pushes to the tracked branch (without an associated pull request) will not trigger runs. If this behavior is not desired for your workflow, you'll need to evaluate whether the benefits of having reliable pull request ID availability outweigh this limitation.

Canceling in-progress runs»

You can use push policies to pre-empt any in-progress runs with the new run. The input document includes the in_progress key, which contains an array of runs that are currently either still queued, ready, or awaiting human confirmation. You can use it in conjunction with the cancel rule like this:

1 2 3 | |

1 | |

Of course, you can use a more sophisticated approach and only choose to cancel a certain type of run, or runs in a particular state. For example, this rule will only cancel proposed runs that are currently queued (waiting for the worker):

1 2 3 4 5 | |

1 2 3 4 5 | |

You can also compare branches and cancel proposed runs in queued state pointing to a specific branch:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Cancelation restrictions»

There are some restrictions on cancelation:

- Module test runs cannot be canceled. Only proposed and tracked stack runs can be canceled.

- Cancelation works based on a new run pre-empting existing runs. What this means is that if your push policy does not result in any runs being triggered, the cancelation will have no effect.

- A run can only cancel other runs of the same type. For example a proposed run can only cancel other proposed runs, not tracked runs.

- Cancelation is best effort and not guaranteed. If the run is picked up by the worker or approved by a human in the meantime, the cancelation itself is canceled.

Configuring Ignore event behavior»

Customize VCS check messages for Ignored Run events»

To customize the messages sent back to your VCS when Spacelift runs are ignored, use the message function within your Push policy. See the example policy for reference.

Customize check status for Ignored Run events»

By default, ignored runs on a stack will return a skipped status check event, rather than a fail event. If you want ignored run events to have a failed status check on your VCS, set the fail function value to true in your Push policy.

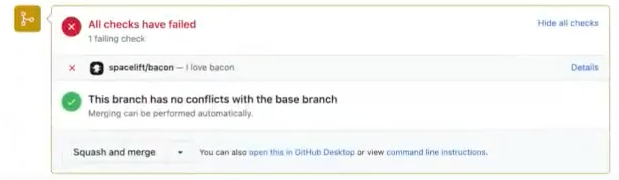

Example policy»

The following push policy does not trigger any run within Spacelift. Using this policy, we can ensure that the status check within our VCS (in this case, GitHub) fails and returns the message "I love bacon."

1 2 | |

1 2 | |

With this policy, users would see this behavior within their GitHub status check:

Info

This behavior (customization of the message and failing of the check within the VCS), is only applicable when runs do not take place within Spacelift.

Tag-driven Terraform module release flow»

You can use a simple push policy to manage your Terraform module versions using git tags and push your module to the Spacelift module registry using git tag events. Use the module_version block within a push policy attached your module, and then set the version using the tag information from the git push event.

For example, this push policy will trigger a tracked run when a tag event is detected, then parses the tag event data and uses that value for the module version. We remove a git tag prefixed with v as the Terraform module registry only supports versions in a numeric X.X.X format.

For this policy, you will need to provide a mock, non-existent version for proposed runs. This precaution has been taken to ensure that pull requests do not encounter check failures due to the existence of versions that are already in use.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

To add a track rule to your push policy, this will start a tracked run when the module version is not empty and the push branch is the same as the one the module branch is tracking:

1 2 3 4 | |

1 2 3 4 | |

Allow forks»

By default, Spacelift doesn't trigger runs when a forked repository opens a pull request against your repository. This is to prevent a security incident. For example, if your infrastructure were open source, someone could fork it, implement unwanted code, then open a pull request for the original repository that would automatically run.

Info

The cause is very similar to GitHub Actions, where they don't expose repository secrets when forked repositories open pull requests.

If you want to allow forks to trigger runs, you can explicitly do it with allow_fork rule. For example, if you trust certain people or organizations, this rule allows a forked repository to run only if the owner of the forked repo is johnwayne or microsoft:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

1 2 3 4 5 | |

The head_owner field means different things in different VCS providers:

| VCS provider | Meaning of head_owner field |

Where to find it |

|---|---|---|

| GitHub/GitHub Enterprise | The organization or person who owns the forked repo. | In the URL: https://github.com/<head_owner>/<forked_repository>. |

| GitLab | The group of the repository. | In the URL: https://gitlab.com/<head_owner>/<forked_repository>. |

| Azure DevOps | The ID of the forked repo's project (a UUID). | Open https://dev.azure.com/<organization>/_apis/projects in your browser to see all projects and their unique IDs. |

| Bitbucket Cloud | Workspace. | In the URL: https://www.bitbucket.org/<workspace>/<forked_repository> |

| Bitbucket Datacenter/Server | The project key of the repo. | The display name of the project and its abbreviation (all caps). |

Approval and mergeability»

The pull_request property on the input to a push policy contains the following fields:

approved: Indicates whether the PR has been approved.mergeable: Indicates whether the PR can be merged.undiverged: Indicates that the PR branch is not behind the target branch.

This push policy will automatically deploy a PR's changes once it has been approved, any required checks have completed, and the PR has a deploy label added to it:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 | |

Each source control provider has slightly different features, and because of this, the exact definition of approved and mergeable varies slightly.

GitHub / GitHub Enterprise »

approved: The PR has at least one approval, and also meets any minimum approval requirements for the repo.mergeable: The PR branch has no conflicts with the target branch, and any branch protection rules have been met.

GitLab »

approved: The PR has at least one approval. If approvals are required, it is onlytruewhen all required approvals have been made.mergeable: The PR branch has no conflicts with the target branch, any blocking discussions have been resolved, and any required approvals have been made.

Azure DevOps »

approved: The PR has at least one approving review (including approved with suggestions).mergeable: The PR branch has no conflicts with the target branch, and any blocking policies are approved.

Info

We are unable to calculate divergence across forks in Azure DevOps, so the undiverged property will always be false for PRs created from forks.

Bitbucket Cloud »

approved: The PR has at least one approving review from someone other than the PR author.mergeable: The PR branch has no conflicts with the target branch.

Bitbucket Datacenter/Server »

approved: The PR has at least one approving review from someone other than the PR author.mergeable: The PR branch has no conflicts with the target branch.

Data input schema»

As input, Git push policy receives the following:

Official Schema Reference

For the most up-to-date and complete schema definition, please refer to the official Spacelift policy contract schema under the GIT_PUSH policy type.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 | |

New module version schema»

When triggered by a new module version, this is the schema of the data input that each policy request will receive:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 | |

How rules are evaluated»

Based on this input, the policy may define boolean track, propose and ignore rules.

- The positive outcome of at least one

ignorerule causes the push to be ignored, no matter the outcome of other rules. - The positive outcome of at least one

trackrule triggers a tracked run. - The positive outcome of at least one

proposerule triggers a proposed run.

If no rules are matched, the default is to ignore the push. Always supply an exhaustive set of policies, making sure that they define what to track and what to propose in addition to defining what they ignore.

You can also define an auxiliary rule called ignore_track, which overrides a positive outcome of the track rule but does not affect other rules, most notably propose. This can be used to turn some of the pushes that would otherwise be applied into test runs.

Examples»

Tip

We maintain a library of example policies ready to use or alter to meet your specific needs.

If you cannot find what you are looking for below or in the library, please reach out to our support and we will craft a policy to do exactly what you need.

Ignoring certain paths»

Ignoring changes to certain paths is something you'd find useful both with classic monorepos and repositories containing multiple OpenTofu/Terraform projects under different paths. When evaluating a push, we determine the list of affected files by looking at all the files touched by any of the commits in a given push.

Info

This list may include false positives, for example in a situation where you delete a given file in one commit, bring it back in another commit, then push multiple commits at once. This is a safer default than trying to figure out the exact scope of each push.

Imagine a situation where you only want to look at changes to Terraform definitions (in HCL or JSON) inside one the production/ or modules/ directory, and have track and propose use their default settings:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | |

To keep the example readable we had to define ignore in a negative way, per the Anna Karenina principle.

Status checks and ignored pushes»

By default when the push policy instructs Spacelift to ignore a certain change, no commit status check is sent back to the VCS. This behavior is explicitly designed to prevent noise in monorepo scenarios where a large number of stacks are linked to the same Git repo.

However, you may still be interested in learning that the push was ignored, or getting a commit status check for a given stack when it's set as required by GitHub's branch protection rules or your internal organization rules.

In that case, you can use the notify rule to override default notification settings. So if you want to notify your VCS vendor even when a commit is ignored, you can define it like this:

1 2 3 4 5 | |

1 2 3 4 5 | |

Info

The notify rule (false by default) only applies to ignored pushes, so you can't set it to false to silence commit status checks for proposed runs.

Applying from a tag»

Another use case for a Git push policy would be to apply from a newly created tag rather than from a branch. This can be useful in multiple scenarios. For example, a staging/QA environment could be deployed every time a certain tag type is applied to a tested branch, thereby providing inline feedback on a GitHub Pull Request from the actual deployment rather than a plan/test. You could also constrain production to only apply from tags unless a run is explicitly triggered by the user.

Here's an example:

1 2 3 4 | |

1 2 3 4 | |

Set head commit without triggering a run»

The track decision sets the new head commit on the affected stack or module. This head commit is used when a tracked run is manually triggered or a task is started on the stack. In this case, you normally want to have a new tracked run, so that's what we do by default.

However, sometimes you want to trigger tracked runs in a specific order or under specific circumstances either manually or using a trigger policy. So what you want is an option to set the head commit without triggering a run. The boolean notrigger rule will work in conjunction with the track decision and prevent the tracked run from being created.

notrigger does not depend in any way on the track rule; they're entirely independent. Spacelift will only look at notrigger if track evaluates to true when interpreting the result of the policy.

Here's an example of using the two rules together to always set the new commit on the stack, but not trigger a run. You would use this when the run is always triggered manually, through the API, or using a trigger policy:

1 2 3 | |

1 2 3 | |

Default Git push policy»

If no Git push policies are attached to a stack or a module, the default behavior is equivalent to this policy:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 | |

Waiting for CI/CD artifacts»

There are cases where you want pushes to your repo to trigger a run in Spacelift, but only after a CI/CD pipeline (or a part of it) has completed. An example would be when you want to trigger an infra deploy after some Docker image has been built and pushed to a registry.

You can use push policies' external dependencies feature to achieve this.

Prioritization»

Although we generally recommend using our default scheduling order (tracked runs and tasks, then proposed runs, then drift detection runs), you can use push policies to prioritize certain runs over others. For example, you may want to prioritize runs triggered by a certain user or a certain branch.

Use the boolean prioritize rule to mark a run as prioritized:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | |

1 2 3 4 5 | |

This example will prioritize runs on any stack that has the prioritize label set. Run prioritization only works for private worker pools. An attempt to prioritize a run on a public worker pool using this policy will not work.

Stack locking»

Stack locking can be particularly useful in workflows heavily reliant on pull requests. The push policy enables you to lock and unlock a stack based on specific criteria using the lock and unlock rules.

lock rule behavior when a non-empty string is returned:

- Lock the stack if it's currently unlocked.

- No change if the stack is already locked by the same owner.

- Reject any runs if the stack is locked by a different owner and you attempt to lock it.

unlock rule behavior when a non-empty string is returned:

- No change if the stack is currently unlocked.

- Unlock the stack if it's locked by the same owner.

- No change if the stack is locked by a different owner.

Info

Runs are only rejected if the push policy rules result in an attempt to acquire a lock on an already locked stack with a different lock key. If the lock rule is undefined or results in an empty string, runs will not be rejected.

This example policy snippet locks a stack when a pull request is opened or synchronized, and unlocks it when the pull request is closed or merged.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

You can customize selectively locking and unlocking the stacks whose project root or project globs are set to track the files in the pull request:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | |

You can also lock and unlock through comments:

1 2 3 4 | |

1 2 3 4 | |

You can then unlock your stack by commenting something such as:

1 | |